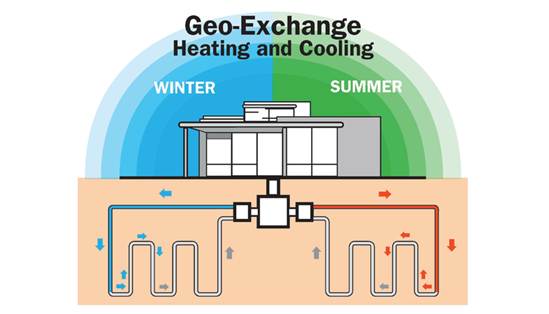

Geo-exchange heating and cooling uses the Earth’s stable underground temperatures to efficiently regulate indoor climates. In a nutshell, the system extracts heat from the ground and transfers it indoors in the colder months and removes heat from the building and releases it into the ground in warmer months. This process relies on underground piping (ground loops) and a heat pump to facilitate the exchange of thermal energy (Geothermal Technologies Office). In recent times, The Lawrenceville School has taken great efforts to make their campus buildings more energy efficient and cost effective. The campus heating system recaptures more than 90% of the steam used to heat campus buildings, however, there is still a large dependence on natural gas (The Lawrenceville School).

Another local school community which has tried to reduce their carbon footprint over the years is Princeton Day School. Similarly to Lawrenceville, PDS relies heavily on natural gas alongside what would be considered much cleaner heating and cooling methods. As it is for any major project, it requires a ton of time, money, and labor to realise a realistic change, and a significant benefit found in the long run.

The Kirby Math and Science building (20,000 sq ft), for example, is LEED certified — a globally recognized symbol of sustainability achievement (The Stephan Archives). For the sake of simplicity, the following calculation will account for the building being heated and cooled explicitly by natural gas. An initial installation cost to convert the building to be fully geoexchange is a staggering $600,000. This is much more expensive than the cost of natural gas which is $100,000 to implement and is already in place.

According to Mr. Robert Clemens, the Director of Facility Operations at Princeton Day School who has been with the school since 2019, “Princeton University is converting to geo-exchange, their conversion to geo-exchange costs hundreds of millions of dollars to perform and involves driller 2000 wells between 600 and 800 feet deep.” He goes on to say that it is hard to say when their anticipated payback will be but most documentation we have researched shows the typical payback on a geo-thermal exchange system is under a decade. A payback period of only ten years does not sound bad but that large upfront cost is most definitely digging into any budget, even of the wealthiest schools like Princeton University’s. But it is also interesting to see the efficiency of geo-echange being that it is such a cleaner method of heating and cooling compared to others.

It is actually seen that Geothermal heat pumps are significantly more efficient than natural gas furnaces. Geothermal heat pumps operate at a 300-500% efficiency compared to natural gas’ 90-98% efficiency (National Heating & Air Conditioning). This means that for every 1 unit of electricity used, geo-exchange produces 3 to 5 units of heat — much more than that of fossil fuels. Geo-exchange is made so efficient because it transfers heat rather than generates it by burning fuel, allowing it to achieve much higher efficiency.

As Lawrenceville looks to do, PDS is also looking for a way to reduce their carbon footprint and convert to cleaner means of energy. The primary problem is the initial cost, as mentioned before, which prevents Lawrenceville from completely transitioning. Geo-exchange, although it looks like a good option, is not the only alternative to heating and cooling. Mr. Clemens states that the school “upgraded our ice rink chiller 2 years ago, we also needed to replace the dehumidification system that serves the ice rink. Prior to this, the system utilized natural gas to perform this process. Now the school is about to recycle waste heat to the ice rink chiller plant to dehumidify our ice rink showing great bounds in cleaner energy”. This method is a good starting place for a long term change and is something that Lawrenceville could do. Another example of PDS increasing their energy efficiency recently is one of their “smaller building’s natural gas heating and air conditioning systems failed and [they] took the opportunity to install an electric air to air heat pump, which does not use natural gas and is more energy efficient than a gas fired furnace.” It’s reassuring knowing that strides are always being taken by communities such as Lawrenceville to prioritize sustainability and reduce reliance on fossil fuels. By implementing cleaner technologies like waste heat recycling and electric heat pumps, schools like PDS and Princeton University are setting an example for how smaller communities and institutions can transition toward greener energy solutions. Efforts such as these not only lower carbon emissions but also improve long-term energy efficiency and cost effectiveness, demonstrating a commitment to environmental responsibility and benefit over the long run in more ways than one. As Lawrenceville explores similar initiatives, it is encouraging to see the broader shift toward sustainable infrastructure, ensuring that future generations inherit cleaner and more energy-efficient campuses. A larger shift to more energy efficient ways of maintaining buildings from natural gas could enormously help to reduce the temperature increase of the planet due to climate change.

How GeoExchange works:

Cost of installing the Geo-Exchange system for only one household:

Impact onto the world if energy efficiency was increased and natural gas taxed: